How often does something work exactly as planned, and live up to its hype? In most of the world, that's the equivalent of stumbling across a unicorn that's holding a few winning lottery tickets in its teeth. But that pretty much describes our top science story of 2022, the successful deployment and initial images from the Webb Telescope.

In fact, there was lots of good news to come out of the world of science, with a steady flow of fascinating discoveries and tantalizing potential tech—over 200 individual articles drew in 100,000 readers or more, and the topics they covered came from all areas of science. Of course, with a pandemic and climate change happening, not everything we wrote was good news. But as the top stories of the year indicate, our readers found interest in a remarkable range of topics.

10. Fauci on the rebound

For better and worse, Anthony Fauci has become the public face of the pandemic response in the US. He's trusted by some for his personable, plain-spoken advice regarding how to manage the risks of infection—and vilified by others for his advocacy of vaccinations (plus a handful of conspiracy theories). So, when Fauci himself ended up on the wrong end of risk management and got a SARS-CoV-2 infection, that was news as well, and our pandemic specialist, Beth Mole, was there for it.

It turned out the trajectory of his infection was a metaphor for the pandemic itself, where every silver lining seems to be delivered with a few additional gray clouds. Fauci took Paxlovid, a drug that was developed due to some very rapid scientific work that involved finding out the structure of viral proteins and then identifying molecules that could fit into that structure. As a result of its design, Paxlovid rapidly and effectively suppresses the SARS-CoV-2 infections that cause COVID-19.

But once again, there are those gray clouds: once the treatment course runs out, many people experience a rebound of symptoms for reasons we're still working out. And Fauci was no exception, having symptoms severe enough that he went back on the drug to shut them down again—even though that's not been recommended by the Food and Drug Administration.

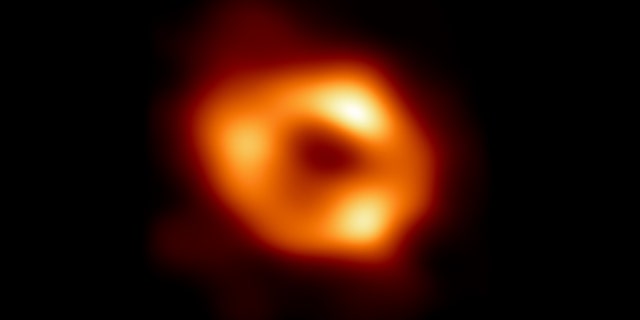

9. Fear the magnetar

Neutron stars are probably the most extreme objects in the Universe (black holes being more of an aberration in spacetime than an object, per se). They're places where the tallest "mountains" are less than a millimeter, and cracks in the crust can create violent bursts of radiation. They're also places where the interior is a superfluid of rapidly circulating subatomic particles.

But in a handful of these stars, conditions get even more extreme, as any charged particles in the superfluidic interior can create a dynamo like the one in the Earth's core that creates our magnetic field. Except just a bit stronger. Well, as Paul Sutter details it, 1016 times stronger. These are the magnetars, a short-lived state of some neutron stars (they last about 10,000 years, which is short for astronomy).

There are plenty of ways a neutron star can kill you, given its intense gravity and tendency to spew out lethal levels of radiation. But magnetars have an additional trick: they end chemistry. The magnetic fields are so strong that they can distort the atomic orbitals that determine how different atoms latch on to each other to form chemical bonds. Get within 1,000 kilometers or so of a magnetar, and that distortion gets so severe that the chemical bonds no longer function. All your atoms are left free to wander around as they see fit, which isn't generally conducive to life.

8. The SLS: a mixed triumph?

This article was a personal rumination by Eric Berger, reflecting on the changes in NASA and the launch industry since he started covering both roughly two decades ago. For most of that time, NASA's budget has been dominated by the Space Launch System, which finally took its maiden flight this year, sending hardware to orbit the Moon and return for a flawless splashdown.

In the wake of that launch, you might expect that the piece would focus on that success. Instead, Berger argued that the many failures of the program—countless delays and cost overruns—changed the entire launch industry, giving small companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin a chance to thrive while their entrenched competitors were focused on getting all they could out of SLS contracts. Without SLS's problems, Berger argues, the vehicles that will eventually see NASA to a successful future of crewed exploration might never have been built.

7. Deep heating

This is one that falls into the "potentially not very good news category." One of the biggest unresolved questions regarding climate change is just how much warming we'll get from the amount of carbon dioxide we've put into the atmosphere. We have a best estimate, but it has significant error bars—a given level of emissions could potentially mean two or four degrees of warming, depending on whether the real value is on the low end or high end of those error bars.

There are a number of ways to narrow down those error bars, and Howard Lee looks at one of the simplest: looking at the past to find instances where the levels of carbon dioxide were different, and figure out the temperatures. Get enough of these, and you might narrow down the range of uncertainty, even if our ability to get accurate measurements of the past is necessarily a bit limited.

That process is what this story is about. We thought we had a good handle on the temperatures during the Eocene, tens of millions of years ago. But a new technique, applied to deep ocean sediments, indicates the temperatures were considerably warmer than previous estimates. What that means for the temperature of the planet's atmosphere is less certain, but it definitely implies that it might have been warmer than we knew. And that could mean the planet is more sensitive to greenhouse gasses than we thought.

6. A belated exoneration

Robert Oppenheimer was central to the US' production of an atomic bomb during World War II. A physicist at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was tapped to head Los Alamos National Lab during the Manhattan Project, and he oversaw the first test of the device in the New Mexico desert. After the war, he went on to chair the US' Atomic Energy Commission, where he advocated for international policies that limited nuclear proliferation.

But, as Jennifer Ouellette describes, Oppenheimer ran afoul of the politics of his day. His advocacy of liberal causes in the prewar years brought him into association with communists in the Berkeley community—associations that came to the forefront during the Red Scare of the 1950s. At that point, his promotion of nuclear arms limits and opposition to the development of the hydrogen bomb raised further suspicions, which eventually led to his security clearance being revoked, which in turn sidelined him from nuclear policy discussions and cast a cloud over his later career.

While there was some movement to restore Oppenheimer's reputation while he was still alive, it took until this year for the US government to formally acknowledge that revoking his security clearance was a mistake. Oppenheimer won't get to enjoy the restoration of his security clearance, but his family can enjoy the fact that a dark stain has been lifted from a remarkable career.

5. The helicopter that won't quit

For those of us who might be inclined to reject the contention that we live in remarkable times, I'd like to remind you that we currently have an operational helicopter on Mars—earlier this month, Ingenuity completed its 37th flight. Its success not only altered how we're approaching the exploration of Mars but is changing plans for how we might perform future missions.

Back in May, however, the future was less certain, with communications with Ingenuity lost. The helicopter was simply a demonstration project, meant to show that this was something that could help with future exploration. But, as Eric Berger writes, it had become central to the mission of the Perseverance rover—so much so that work of Perseverance was put on hold so it could devote its resources to try to reestablish communication with the helicopter. Obviously, given that Ingenuity is still flying, it worked.

4. Last splash?

It's a problem that roughly half of us have experienced: you're facing a urinal in a public toilet and, no matter how you angle or direct things, a series of splashes keep coming back out in your direction. You might think that after decades of design, this would be a solved problem, but finding a single solution that works for every user's height and—shall we say "stream properties"—turns out to be an open question.

Fortunately, it's a question of fluid mechanics, placing it firmly in the realm of physics. And, as Jennifer Ouellette detailed, more than one research group has found the problem fascinating. I hesitate to suggest that the most recent solution is going to last as the "best" solution, but it has got one thing going for it: it's based on the nautilus, which builds a shell that conforms to the Golden Ratio, a mathematical concept that seems to show up everywhere. So why not urinals?

3. Keep your pants on

People interested in old pants can take a look in the back of one of my closet's shelves. But if you want really old pants, then you should check in with Kiona Smith, who has you covered with the oldest pants yet discovered—over 3,000 years old. Found in western China, the pants may seem like a strictly archeological story. But there's also a mix of engineering, materials science, and human anatomy thrown into the mix, given how the pants are constructed.

The pants were constructed from different weaves and thicknesses, with the shape and material focused on the needs of someone who spent much of their time on horseback. Patterns woven into the fabric suggest that they originated in a culture that could have had widespread interactions with other areas of Asia. All in all, much more information than you might expect from a lone pair of pants.

2. Whose rocket is that, anyway?

Earlier this year, the upper state of an older rocket had a run in with the Moon. We've sent a fair bit of hardware towards the Moon over the years, and weren't especially careful about disposal of used hardware in the early years, so on its own, this wasn't much of a shock. But a search of known trajectories suggested that the hardware was actually recent, and was put in that trajectory when SpaceX launched a satellite for NOAA.

Even before Elon Musk's spectacular fall from grace in recent months, this elicited a fair bit of chortling. But that chortling was apparently misdirected. After a suggestion that the trajectories didn't actually work out, the original source of the SpaceX ID went back further, and found that the hardware was likely to be from an early Chinese Moon mission. With a better match in hand, SpaceX was let off the hook.

Regardless of the source, the Moon ended up struck but declined to comment for the story.

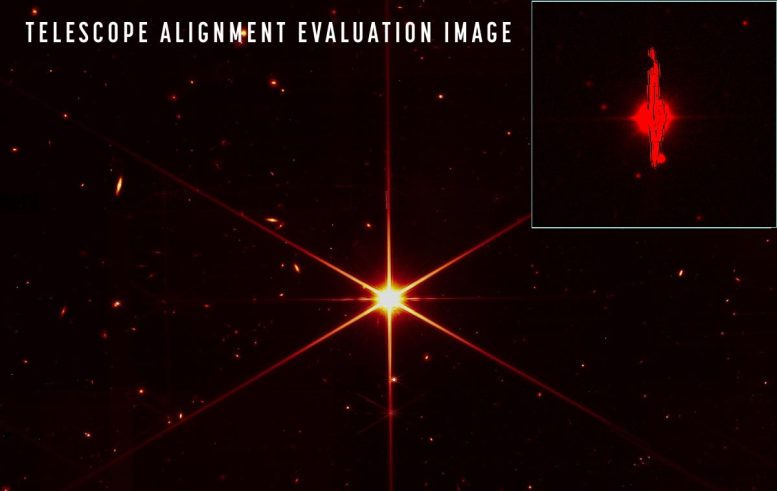

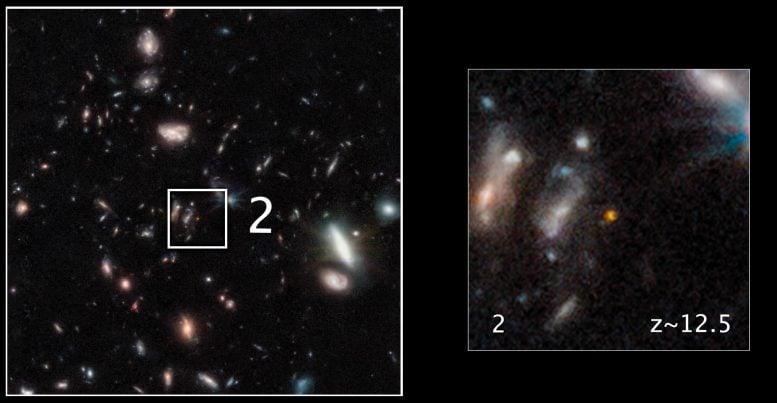

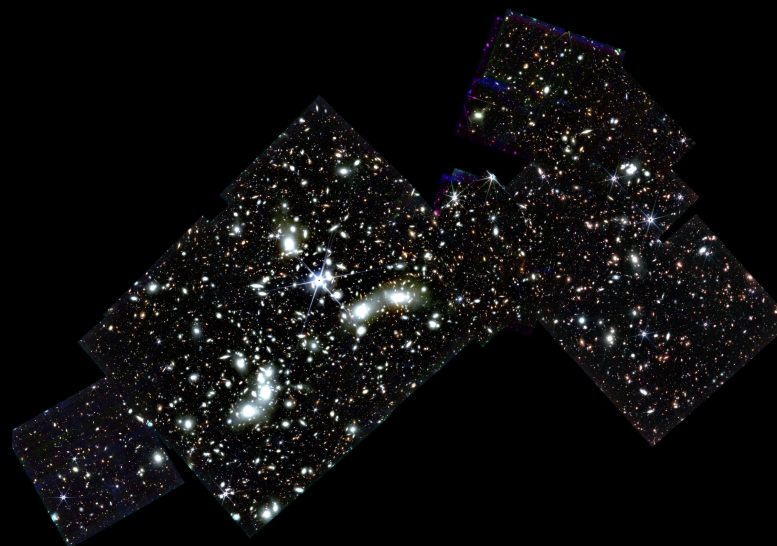

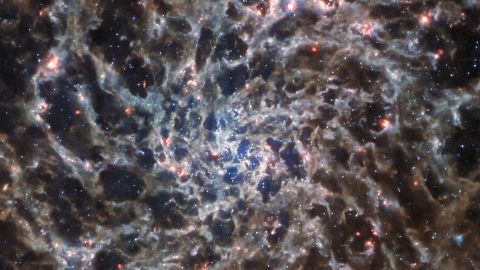

1. The start of the JWST era

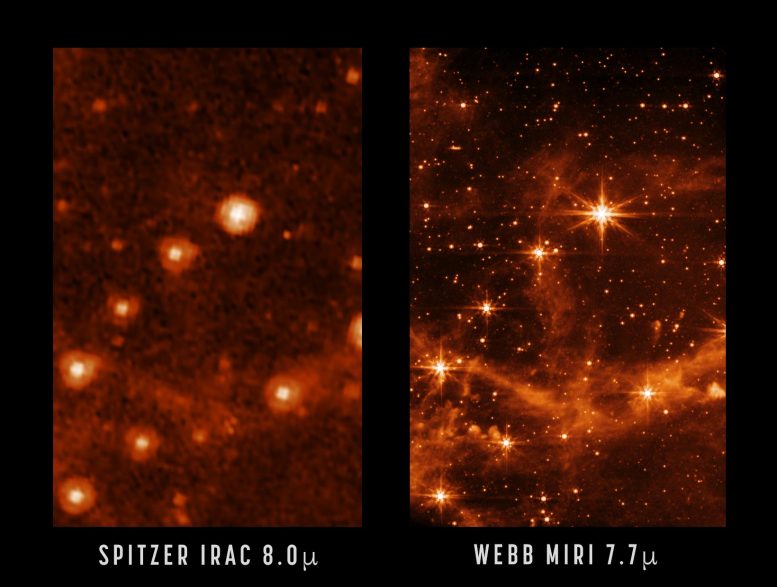

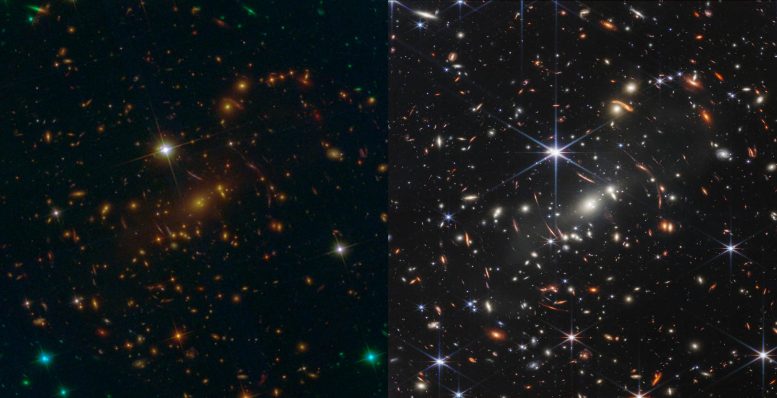

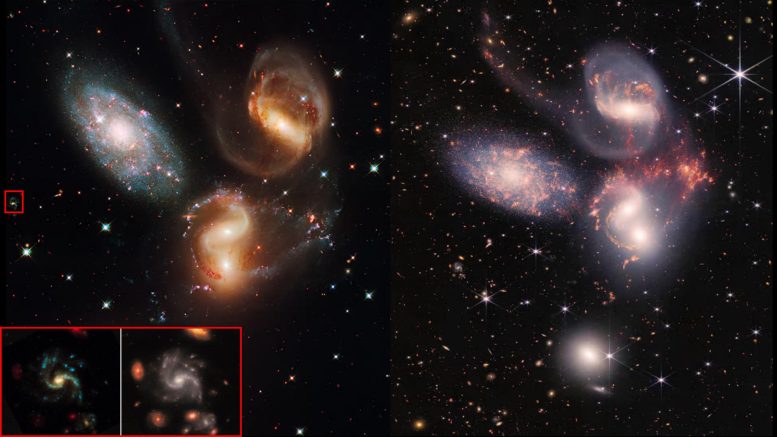

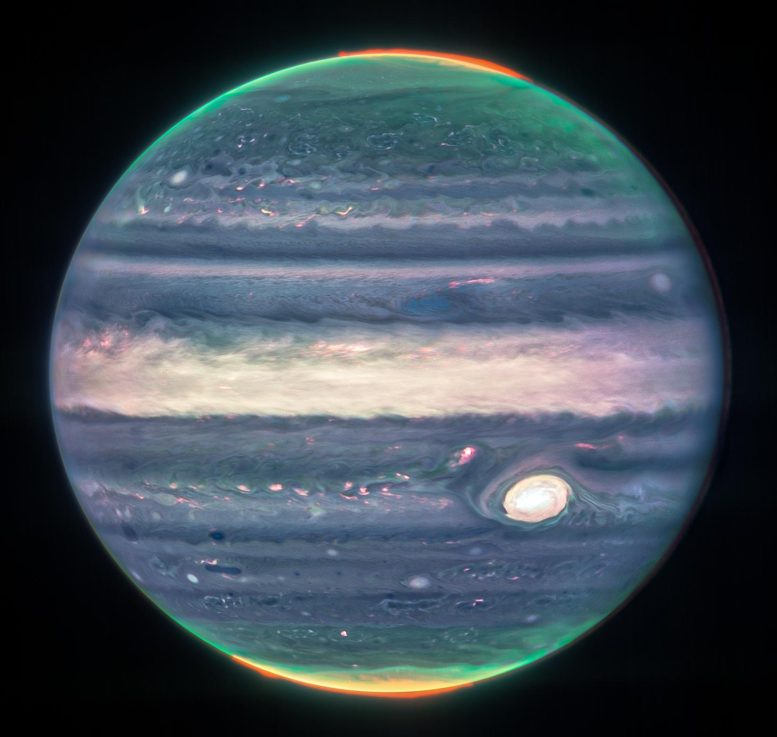

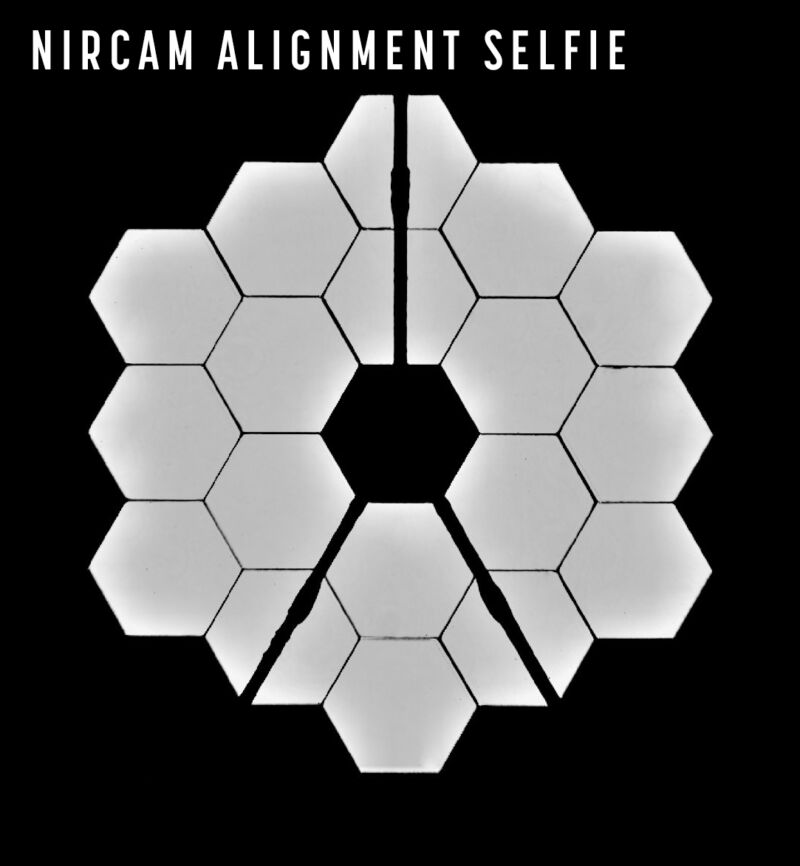

The year's most popular story was probably the best science story of the year: the Webb Telescope's successful commissioning and the images that resulted. Launched around this time last year, the hardware had to undergo a months-long series of self-assembly steps in space, any one of which could have failed and left the observatory a useless piece of space junk. Every single one went off without a hitch.

Those of us around for the Hubble's launch will remember the sinking disappointment when the images that came down didn't in any way reflect the promises of the hardware's design. In this case, as detailed in this piece by Eric Berger, the images lived up to every bit of Webb's promise. The months of aligning all the hardware after self-assembly created an observatory that actually exceeded design specifications, and the images showed it. Even the backgrounds of many subjects contained distant yet clearly resolved galaxies.

Science has already begun, with lots of draft manuscripts appearing almost as quickly as some of the public data was released to the scientific community. The best news here? All of this is likely to continue for years, because everything about this mission, including the launch trajectory, has seemed to exceed planning goals.

https://ift.tt/wEy6Li1

Science