The cool but inviting waters of the Monterey Bay have long been the cherished turf of carefree surfers and relaxing beachgoers and, of course, seals, seabirds and the occasional humpback.

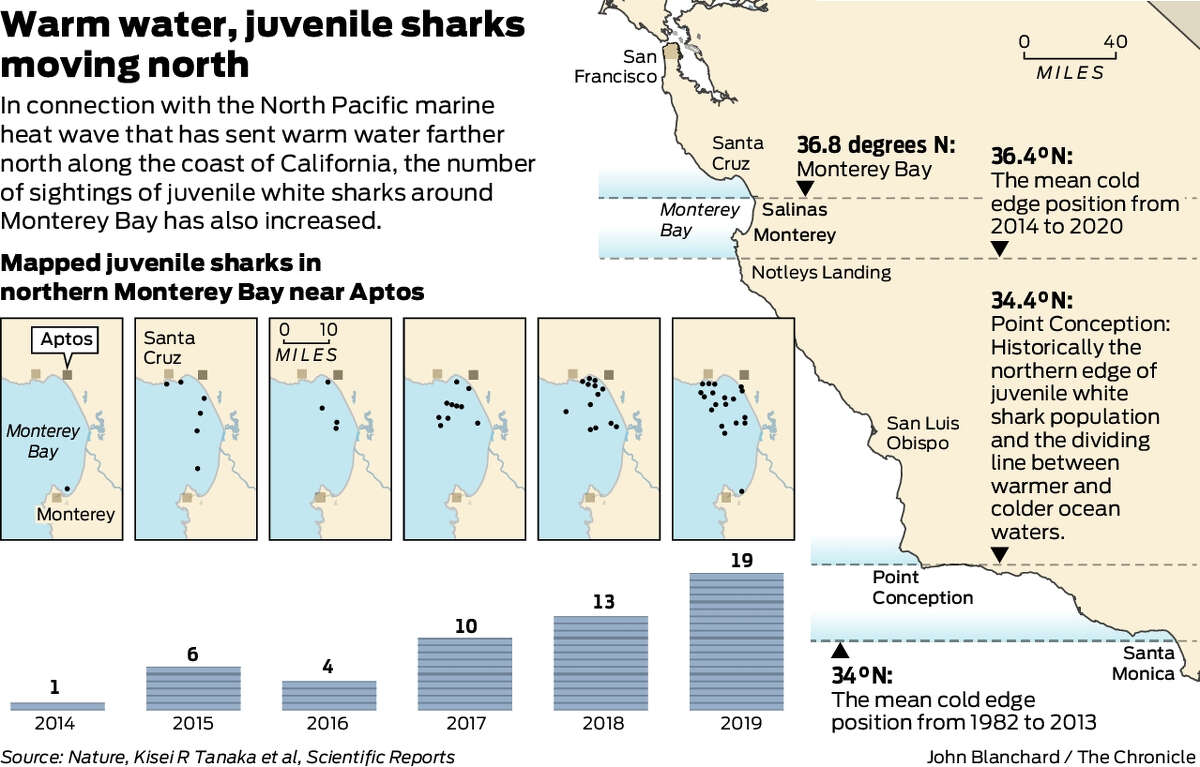

But a few years ago, surprising numbers of young great white sharks began showing up. The apex predators converged largely off the coast of the community of Aptos, swimming so close to shore that sometimes the long, dark frames of a half dozen great whites could be spotted. The summer spectacle, which caught even the best marine scientists off guard, hasn’t let up.

Researchers, in a study published Tuesday, now say they understand why the sharks are there. The young great whites, in another worrisome consequence of climate change, have found that the warming waters of the Monterey Bay have become suitable nursing grounds because of the temperature. Historically, they had preferred the mild conditions of Southern California and northern Mexico.

“From the very beginning, we identified that this is not a shark paper. This is a climate paper,” said Kyle Van Houtan, chief scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium and one of the authors of the new study in the journal Scientific Reports. “These sharks, by venturing into territory where they have not historically been found, are telling us how the ocean is being affected by climate change.”

By analyzing the whereabouts of more than a dozen electronically tagged sharks, the large collaborative of researchers behind the paper found that prior to 2014 the preferred range of the animal went as far north as Santa Barbara. But after a marine heat wave known as “the Blob” hit the Pacific that year, the favorable conditions, marked by temperature, shifted north as far as Bodega Bay and the sharks followed, according to the tracking tags and observations by fishermen and others.

While the Blob has largely dissipated, Monterey Bay, and particularly the waters near Aptos, have remained warmer and more hospitable to the young sharks. Ocean temperatures in the area average about 55 degrees Fahrenheit but have risen as high as 69 degrees in recent years.

The juveniles like these warmer conditions because they’re smaller than the adults, less than 10 feet in length, and don’t regulate their temperature as well. They tend to nurse in shallow coastal waters where they feed on fish, skates and rays. Once they’re 2 or 3 years old and approach their full size of up to 20 feet and several thousand pounds, they strike out for colder, deeper water, including such notorious shark hotbeds as the Farallon Islands.

The study’s authors say the great whites in Monterey Bay aren’t much interested in humans. However, in May of last year, a 26-year-old surfer was fatally bitten not far offshore of Manresa State Beach in Aptos, one of few attacks in the area’s history.

“You put more sharks in the water, you put more people in the water, your probability of an encounter goes up,” said Chris Lowe, professor of marine biology at California State University Long Beach and a co-author of the paper. “But so far what we’ve seen, it appears that the sharks completely ignore people. They just don’t care.”

In recent years, heaps of photos and videos taken along the Santa Cruz County coast have showed unsuspecting swimmers, surfers and paddleboarders coming within a few yards of the young sharks.

Many in the area have begun calling the waters around Seacliff State Beach in Aptos, marked by a marooned oil tanker and landmark known as the Cement Ship, “Shark Park.” The 5- to 9-foot juveniles are typically present between April and October.

Gabe McKenna, public safety superintendent for the regional state parks office, said local lifeguards have taken note of the rise in sharks and respond accordingly, at times posting warnings for visitors and on the rare occasion closing a beach.

“Our aquatics staff is really proactive with all components of aquatic safety,” McKenna said.

Partly because of the rise in shark numbers, the state has provided funding for increased monitoring of the great whites. A pilot program in Southern California using transmitters on buoys to alert lifeguards to the presence of tagged sharks is being considered for Santa Cruz County.

Kurtis Alexander is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: kalexander@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @kurtisalexander

https://ift.tt/3rAV99G

Science

No comments:

Post a Comment