Scientists have long struggled to solve the puzzle of the gearing system on the front of the so-called Antikythera mechanism—a fragmentary ancient Greek astronomical calculator, perhaps the earliest example of a geared device. Now, an interdisciplinary team at University College London (UCL) has come up with a computational model that reveals a dazzling display of the ancient Greek cosmos, according to a new paper published in the journal Scientific Reports. The team is currently building a replica mechanism, moving gears and all, using modern machinery. You can watch an extensive 11-minute video about the project here (embedding currently disabled).

"Ours is the first model that conforms to all the physical evidence and matches the descriptions in the scientific inscriptions engraved on the mechanism itself," said lead author Tony Freeth, a mechanical engineer at UCL. "The Sun, Moon, and planets are displayed in an impressive tour de force of ancient Greek brilliance."

“We believe that our reconstruction fits all the evidence that scientists have gleaned from the extant remains to date,” co-author Adam Wojcik, a materials scientist at UCL, told the Guardian.

The hand-powered Antikythera mechanism has a long history. In 1900, a Greek sponge diver named Elias Stadiatis discovered the wreck of an ancient cargo ship off the coast of Antikythera island in Greece. He and other divers recovered all kinds of artifacts from the ship. A year later, an archaeologist named Valerios Stais was studying what he thought was just a piece of rock recovered from the shipwreck, but he noticed there was a gear wheel embedded in it. It turned out to be an ancient mechanical device. The Antikythera mechanism is now housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

The 82 surviving fragments of the device were originally housed in a wooden box roughly the size of a shoebox, with dials on the outside, containing a complex assembly of gear wheels within. The largest piece is known as Fragment A, which has bearings, pillars, and a block. Another piece, Fragment D, has a disk, a 63-tooth gear, and plate. The mechanism's very existence offers strong evidence that such technology existed as early as 150-100 BC, but the knowledge was subsequently lost. Similar machines with equivalent complexity didn't appear again until the 18th century. While it was found on a Roman cargo ship, historians believe it is Greek in origin, possibly from the island of Rhodes, which was known for impressive displays of mechanical engineering.

It took decades just to clean the device off, and in 1951, a British science historian named Derek J. de Solla Price began investigating the theoretical workings of the device. Based on X-ray and gamma ray photographs of the fragments, Price and physicist Charalampos Karakalos published a 70-page paper in 1959 in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. Based on those images, Price hypothesized that the mechanism had been used to calculate the motions of stars and planets—making it the first known analog computer.

In 2002, Michael Wright, then curator of mechanical engineering at the Science Museum in London, made headlines with new, more detailed X-ray images of the device taken via linear tomography—which means that only features in a particular plane come into focus, enabling closer inspection and pinning the exact location of each gear. Wright's closer analysis revealed a fixed central gear in the mechanism's main wheel, around which other moving gears could rotate. He concluded that the device was specifically designed to model "epicyclic" motion, in keeping with the ancient Greek notion that celestial bodies moved in circular patterns called epicycles. (This was pre-Copernicus, so the fixed point around which they moved was believed to be the Earth.)

X-ray illumination

Fragment of the Antikythera mechanism, circa 205 BC, housed in the collection of National Archaeological Museum, Athens.Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Image

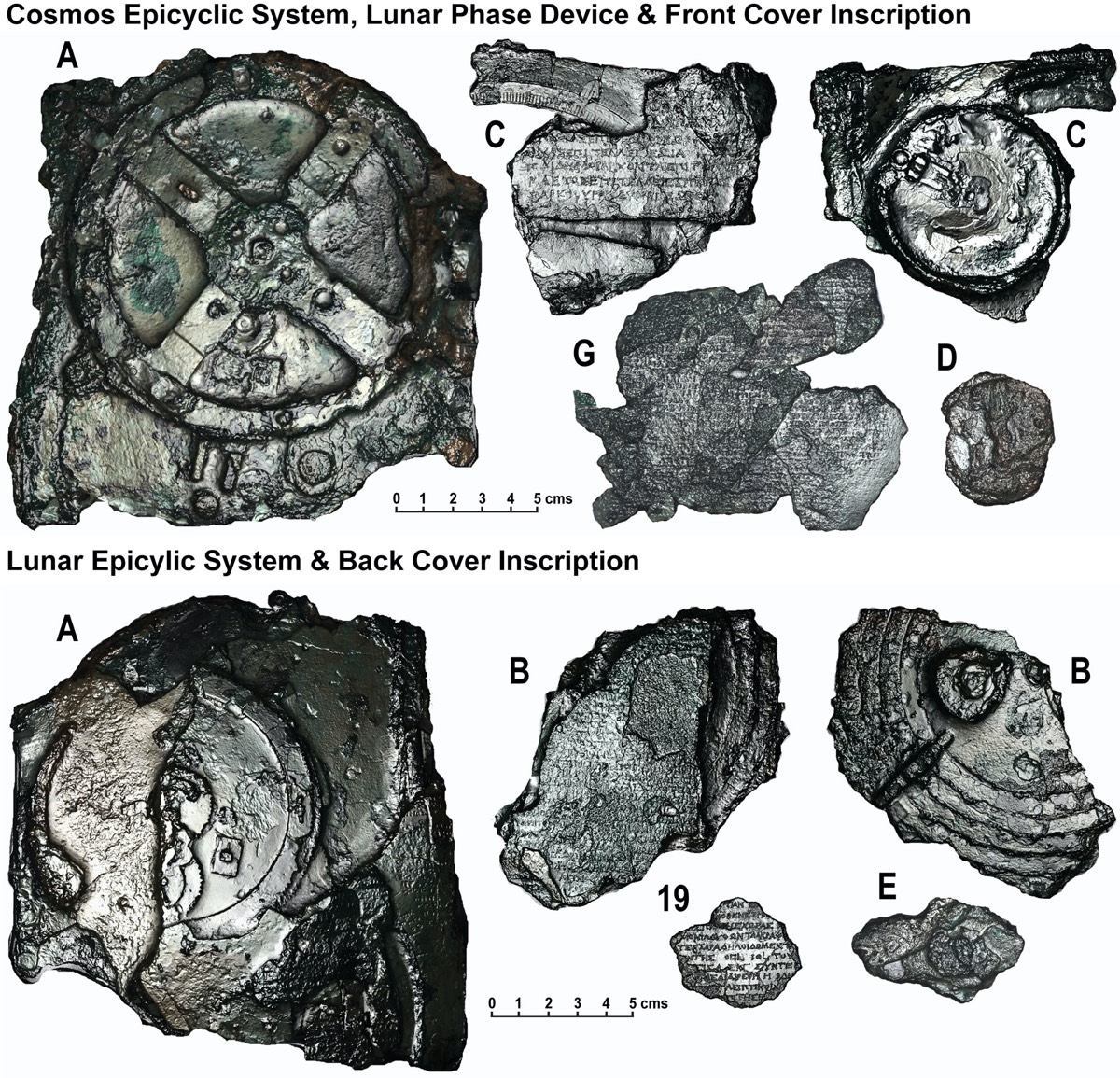

Fragment of the Antikythera mechanism, circa 205 BC, housed in the collection of National Archaeological Museum, Athens.Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Image Fragments of the Antikythera mechanism, enhanced with PTM Dome imaging.Hewlett-Packard, 2005

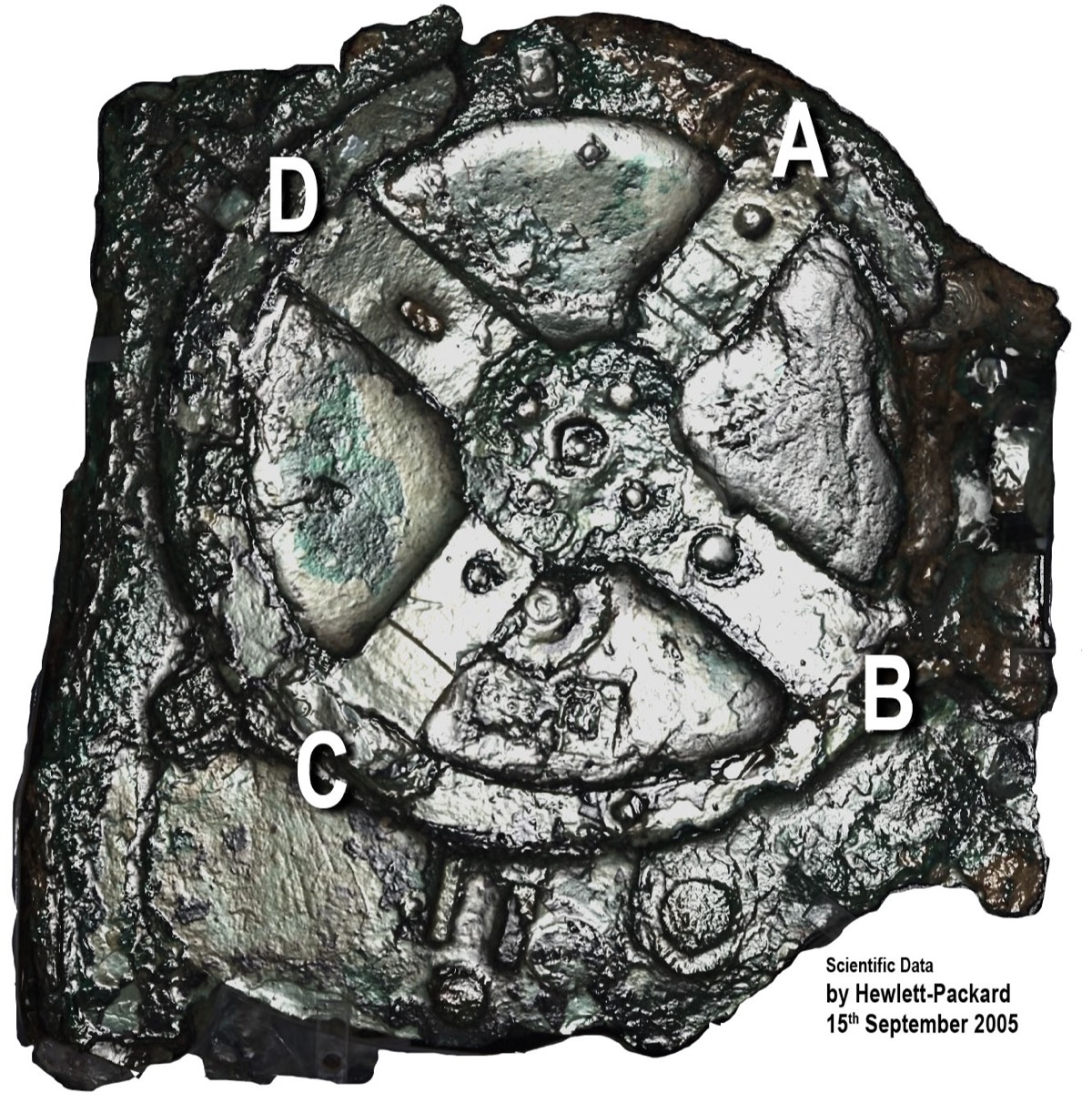

Fragments of the Antikythera mechanism, enhanced with PTM Dome imaging.Hewlett-Packard, 2005 Fragment A, the main surviving fragment, shown using Polynomial Texture Mapping (PTM).Hewlett-Packard, 2005

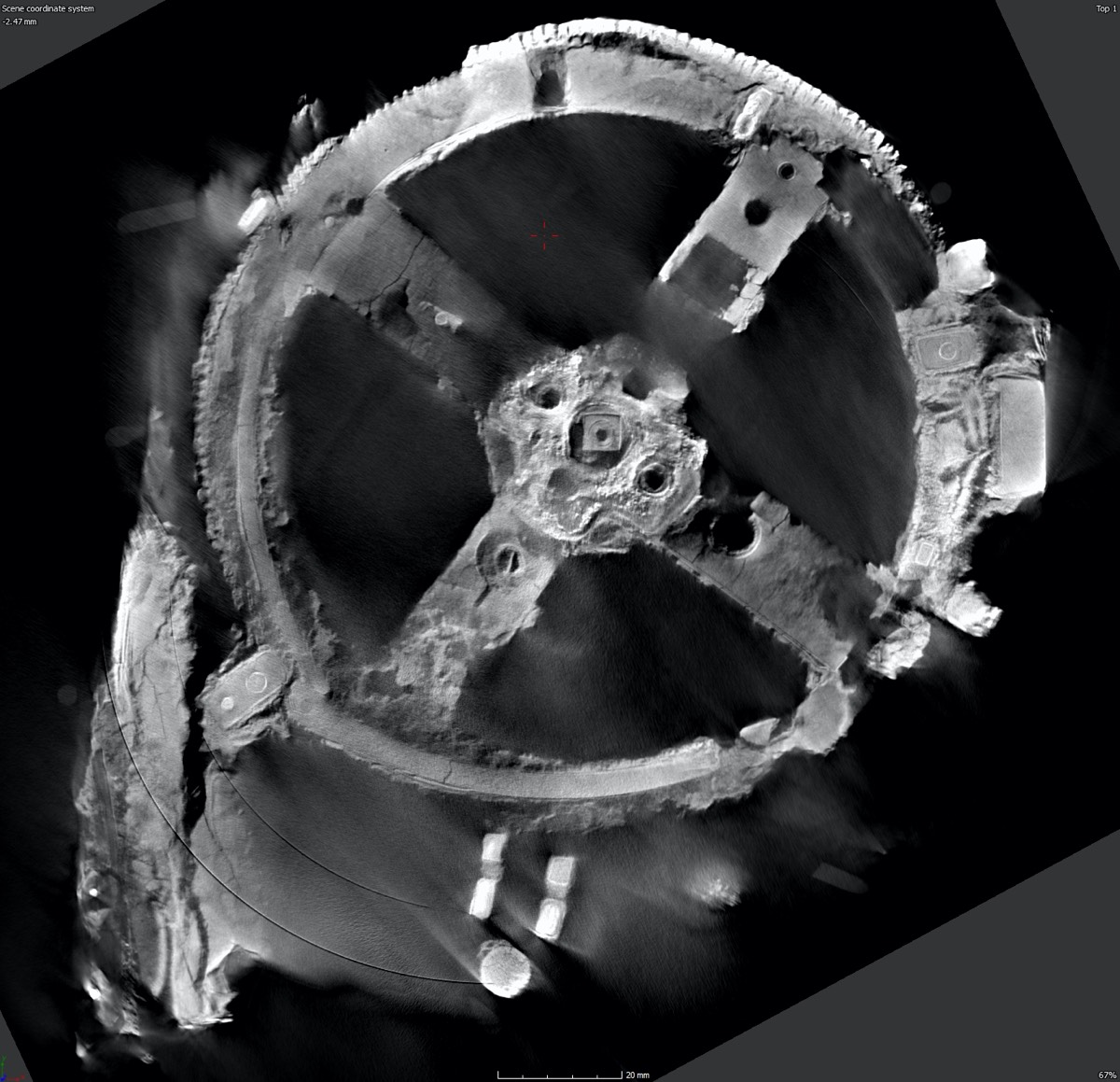

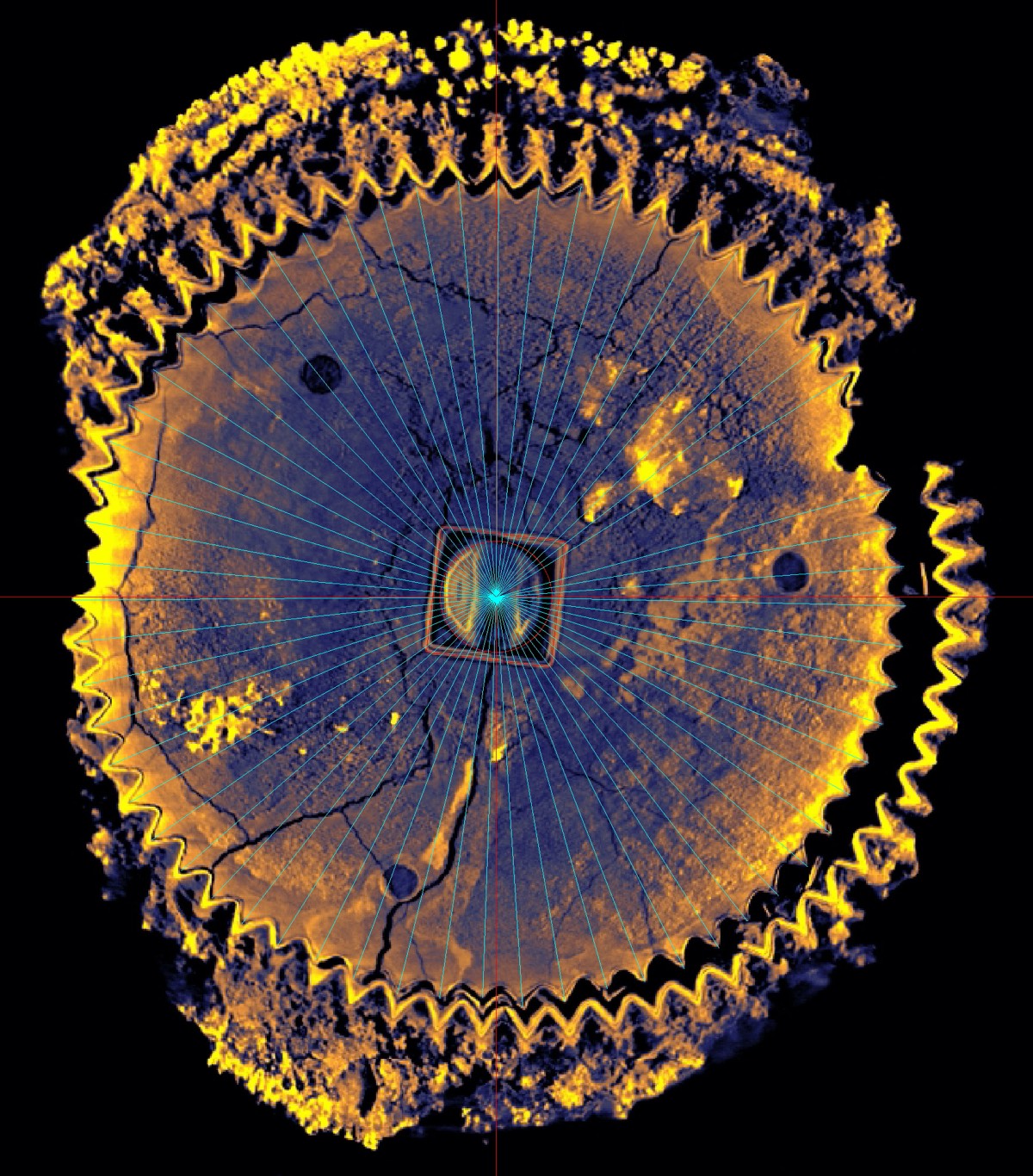

Fragment A, the main surviving fragment, shown using Polynomial Texture Mapping (PTM).Hewlett-Packard, 2005 Fragment A, shown as an X-ray CT slice through the main drive wheel.X-Tek Systems, 2005

Fragment A, shown as an X-ray CT slice through the main drive wheel.X-Tek Systems, 2005 Fragment D shown as a false-color X-ray CT slice, with the teeth tips marked for counting.X-Tek Systems, 2005

Fragment D shown as a false-color X-ray CT slice, with the teeth tips marked for counting.X-Tek Systems, 2005

The device was designed well enough to fairly accurately reproduce the motion of the Sun and Moon, as well as the planets Mercury and Venus. But that leaves out Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, which were also known in antiquity. Wright speculated that there may have been an upper layer to the mechanism, now lost, with extra gears to model the missing planets. He also hypothesized that the lower back dial might have been used to predict eclipses. Wright eventually built a reproduction of the Antikythera mechanism, stacking the gears like layers in a sandwich. By winding a knob along the side, the various celestial bodies could be made to advance and retreat to determine their positions on any chosen dates.

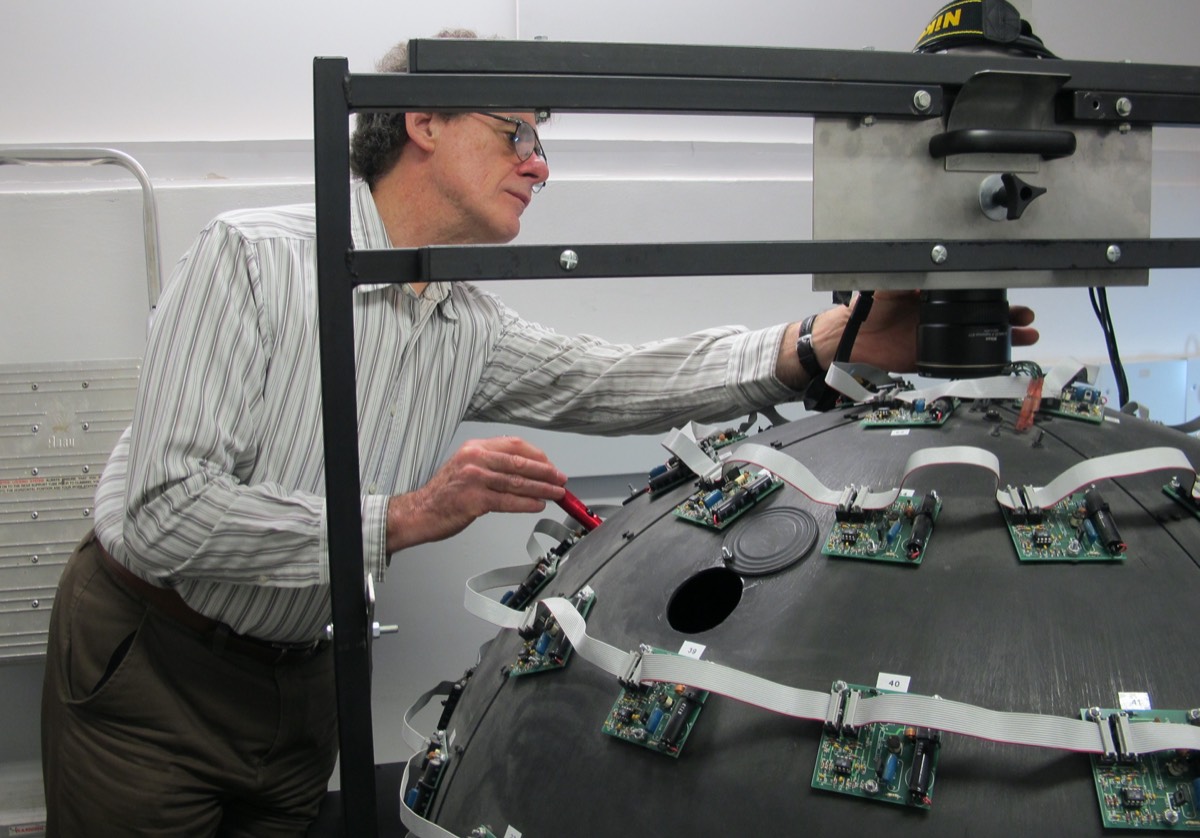

This latest paper builds on Wright's work as part of the ongoing Antikythera Mechanism Research Project, which undertook more advanced 3D X-ray imaging with the help of X-Tek Systems in the UK and Hewlett-Packard, among others. For instance, back in 2005, HP built a new 3D surface imaging device, the PTM Dome, which surrounds the object to be examined—a critical factor, given the fragility of the Antikythera mechanism. X-Tek's contribution was a 12-ton microfocus computerized tomographer. These were used to examine the original fragments, plus additional pieces discovered in October 2005.

A year later, the scientists announced that the new images had revealed much more of the original Greek transcription, which was subsequently translated. These images contained about 1000 characters to 2000 characters, or roughly 95 percent of the surviving text. A reconstruction of the device based on the high-resolution X-ray tomography conducted by the study confirmed it was an astronomical computer used to predict the positions of heavenly bodies in the sky. It's likely that the Antikythera mechanism once had 37 gears, of which 30 survive, and its front face had graduations showing the solar cycle and the zodiac, along with pointers to indicate the positions of the sun and moon.

A model reconstruction

Co-author Tony Freeth examines the Antikythera fragments in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.Tony Freeth

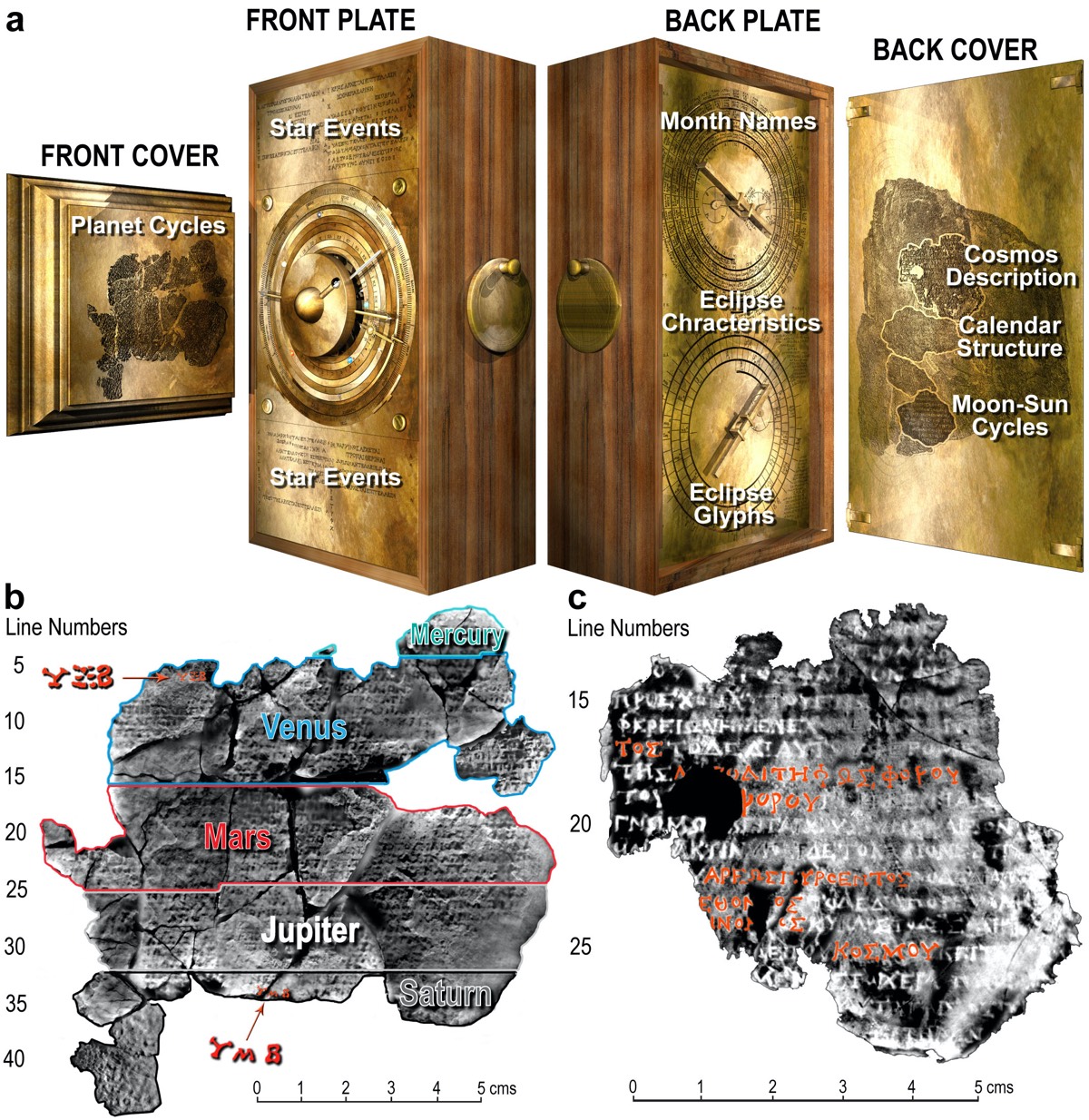

Co-author Tony Freeth examines the Antikythera fragments in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.Tony Freeth Inscriptions on the Antikythera mechanism.Tony Freeth et al. 2021

Inscriptions on the Antikythera mechanism.Tony Freeth et al. 2021 Computer model of the cosmos display on the front of the Antikythera mechanism, showing positions of the Sun, Moon, and five planets, as well as the phase of the Moon and its nodes.Tony Freeth

Computer model of the cosmos display on the front of the Antikythera mechanism, showing positions of the Sun, Moon, and five planets, as well as the phase of the Moon and its nodes.Tony Freeth Another view of the cosmos display.Tony Freeth

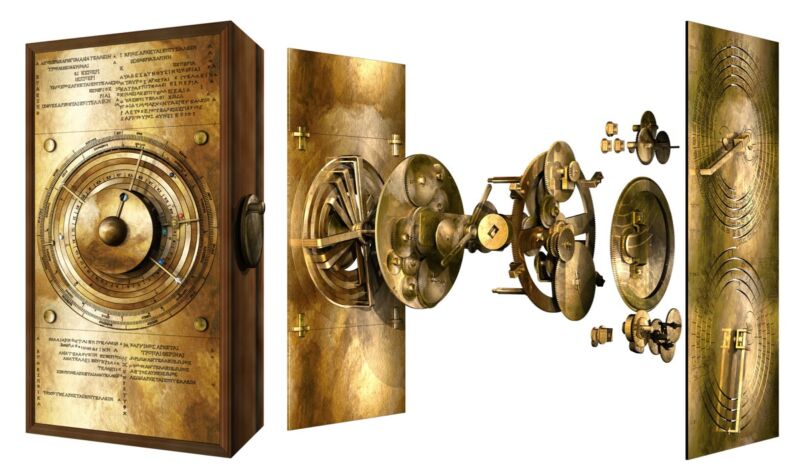

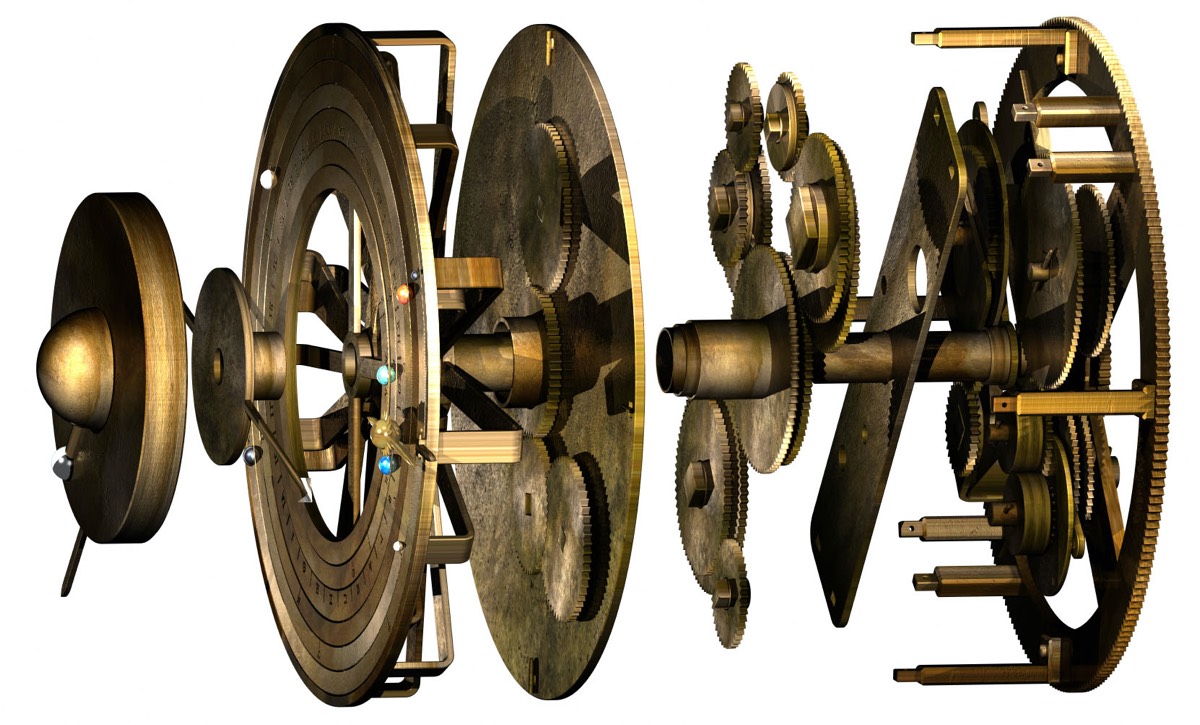

Another view of the cosmos display.Tony Freeth Exploded diagram of the gearing.Tony Freeth

Exploded diagram of the gearing.Tony Freeth Co-author David Higgon making gears.David Higgon

Co-author David Higgon making gears.David Higgon Co-author Myrto Georgakopoulou, an archaeometalurgist, examines some samples.

Co-author Myrto Georgakopoulou, an archaeometalurgist, examines some samples. Co-author and imaging specialist Lindsay Macdonald working on the PTM imaging dome.Lindsay Macdonald

Co-author and imaging specialist Lindsay Macdonald working on the PTM imaging dome.Lindsay Macdonald

Freeth and his co-authors have been working to reconstruct the cosmos display, described in the inscriptions on the mechanism's back cover, featuring planets moving on concentric rings with marker beads as indicators. X-rays of the front cover accurately represent the cycles of Venus and Saturn—462 and 442 years, respectively.

"After considerable struggle, we managed to match the evidence in Fragments A and D to a mechanism for Venus, which exactly models its 462-year planetary period relation, with the 63-tooth gear playing a crucial role," said co-author David Higgon. This enabled the team to derive the cycles of the other planets as well and to create mechanisms to calculate the astronomical cycles while minimizing the number of gears so that everything would fit into the tight space of the device. The team also suggests there may have been a double-ended pointer to predict eclipses, which they have dubbed a "Dragon Hand."

There are still plenty of mysteries surrounding the Antikythera mechanism, however, such as whether this latest version could really have been built using ancient manufacturing techniques. “The concentric tubes at the core of the planetarium [that carried the astronomical outputs] are where my faith in Greek tech falters, and where the model might also falter,” Wojcik told the Guardian. “Lathes would be the way today, but we can’t assume they had those for metal.”

Furthermore, he added, “Although metal is precious, and so would have been recycled, it is odd that nothing remotely similar has been found or dug up. If they had the tech to make the Antikythera mechanism, why did they not extend this tech to devising other machines, such as clocks?"

Nonetheless, "This is a key theoretical advance on how the cosmos was constructed in the Mechanism," said Wojcik. "Now we must prove its feasibility by making it with ancient techniques."

DOI: Scientific Reports, 2021. 10.1038/s41598-021-84310-w (About DOIs).

https://ift.tt/3cphwZP

Science

No comments:

Post a Comment