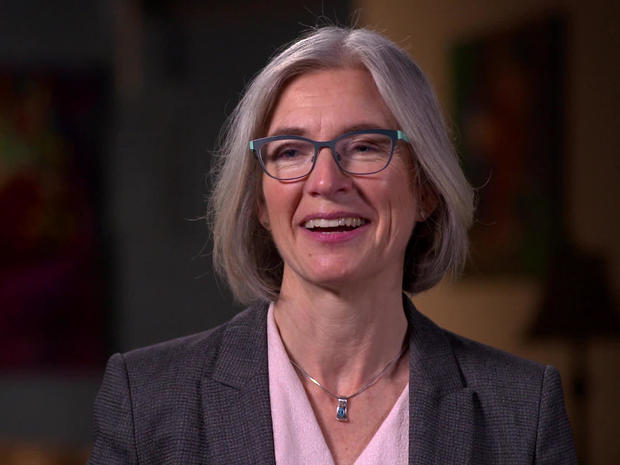

When Jennifer Doudna won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry last year, there was no black-tie ceremony in Sweden. Because of the pandemic, she picked up the medal in her backyard.

Correspondent David Pogue asked Doudna, "Let's cut to the really important thing: Where do you keep your Nobel?"

"Well, truth be told, I have the replica in my house, just a little frame, and have the real medal stashed away in a safe," she replied.

Doudna is a biochemist at the University of California at Berkeley. She and her collaborator, Emmanuelle Charpentier, won the Nobel for their 2012 work on a scientific breakthrough that's frequently described with words like "miraculous": The gene-editing technique known as CRISPR, and acronym for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats.

Pogue asked, "What does it look like in the real world? Is it a computer? Is it software?"

"It's not a computer and it's not software. If you were looking at it in my lab, you would see a tube of colorless liquid," Doudna said.

Two tubes, actually. The first contains molecules that have been engineered to latch onto one particular gene in the cells of a living thing – a specific part of its DNA. The proteins in the other liquid cuts the DNA at that spot. "It's like a zip code that you can address to find a particular place in the DNA of a cell and literally, like scissors, make a snip," said Doudna.

Cutting DNA like this usually disables a gene. We can disable a gene that gives us a disease, or shut off the gene that limits how much fur cashmere goats grow, or how much muscle a beagle grows.

The next step is much harder: Swapping in a different DNA sequence, replacing it with something we've created ourselves. We'll be able to rewrite the genes of any plant, animal or person.

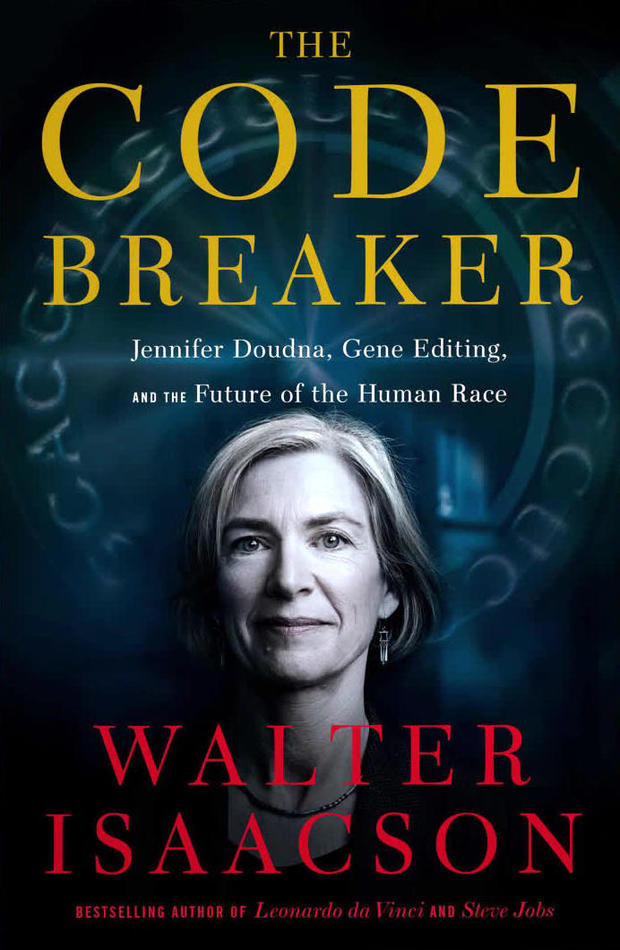

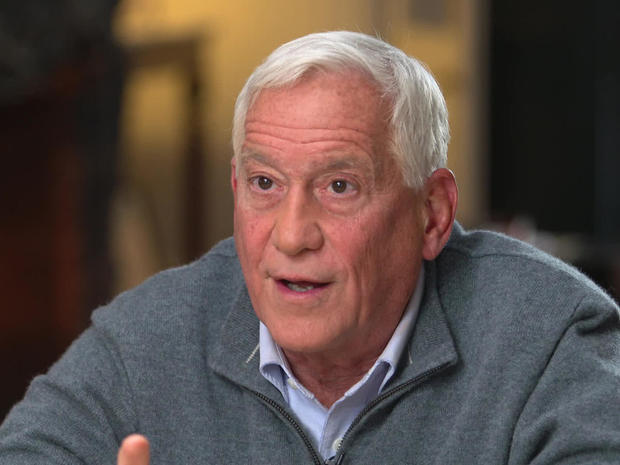

Walter Isaacson is the author of bestselling books about Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein and Steve Jobs. His latest, "The Code Breaker" (published by Simon & Schuster, part of ViacomCBS), is about Jennifer Doudna and her work on CRISPR. "When I started this book, I thought, 'OK, biotechnology and CRISPR, it's the most amazing thing happening in our time,'" Isaacson said. "And then I realized by the end, I was understating the case."

Since Doudna published her paper in 2012, a lot's been going on in the world's CRISPR labs. Scientists have bred more nutritious tomatoes, and created a wheat that doesn't contain gluten. Clinical trials are underway to treat some cancers using CRISPR techniques.

Those medical treatments show off CRISPR's most jaw-dropping possibilities. About 7,000 human diseases are caused by gene mutations that, in theory, we can simply snip away. They include muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, Huntington's disease, and sickle-cell disease, a blood disorder that brings debilitating pain, infections, and early death. It affects about 100,000 Americans, including Victoria Gray, a Mississippi mother of four who became the first American to be treated with CRISPR-fixed genes.

In the year since receiving the experimental treatment, she's had no severe pain or hospitalization.

Of course, like any revolutionary technology, this one has a dark side, with predictions of re-engineered human beings. Pogue asked Doudna, "The headlines are always about, 'Oh, what you've unleashed is designer babies!' Like, people are going to say, 'I want blond, blue-haired, super-smart, super-muscular.' Is that real?"

"Well, yes and no. Mostly no," Doudna replied. "We don't really know which genes need to be edited for the kinds of traits that you mentioned. And I suspect that we're talking about dozens, if not more, genes that would need to be tweaked. Doing that would be technically very challenging. So, I don't think we're on the verge of a world of CRISPR babies myself.

"But it's close enough, in the sense that the technology fundamentally could enable this, that I think it's critical that we have a discussion about it."

Isaacson said, "Most people who have studied this say you got to draw a line between what's medically necessary – in other words, trying to make sure people don't get sickle cell anemia or Huntington's – but it's a blurry line. I mean, if you're trying to improve somebody's memory to make sure they don't have Alzheimer's, you're also improving their memory."

There's also a difference between editing one person's genes, like Victoria Gray's, and making changes that will be passed on to their children.

In 2018, a Chinese doctor edited the embryos of three Chinese babies so that they, and their descendants, would be resistant to the HIV virus. Scientists worldwide condemned him for going rogue.

"In China at first, for about a day, he was celebrated as the first person to create designer babies," Isaacson said. "But even the Chinese were appalled by what he did, and eventually he was tried and put under house arrest."

Since that event, Doudna has been hosting a series of international conferences designed to hammer out ethical guidelines for using CRISPR, so that agreements are in place before a disaster happens.

"Gene editing is a fabulous technology that I think will ultimately help many, many people around the world," she said. "And so to me, it's more a question of managing it."

In the last year, some of the most prominent CRISPR labs, including Doudna's, have turned their attention to a different scientific Holy Grail: Protecting us from COVID, starting with work on a cheap, fast, at-home COVID test.

Doudna said, "I imagine having little CRISPR-based devices so that people can come to work, spit in a tube, and in 30 minutes get an answer, telling them whether they need to be quarantined or not."

In the meantime, scientists all over the world are exploring CRISPR's stunning potential to improve our lives.

Pogue asked Isaacson, "Do you think the biotech revolution will be as big in scope and impact as the digital revolution was?"

"I think the biotech revolution is going to be 10 times more important than the digital revolution, because it allows us to hack the code of life," he replied. "And we shouldn't be afraid of using this technology to make ourselves healthier."

READ A BOOK EXCERPT: "The Code Breaker" by Walter Isaacson

For more info:

- "The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race" by Walter Isaacson (Simon & Schuster), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon and Indiebound

- Walter Isaacson, Tulane University

- Doudna Lab, Berkeley, Calif.

- Innovative Genomics Institute, Berkeley, Calif.

- CRISPR Therapeutics, Cambridge, Mass.

- Sarah Cannon, Nashville, Tenn.

Story produced by Mark Hudspeth. Editor: Steven Tyler.

See also:

https://ift.tt/38hXgIu

Science

No comments:

Post a Comment